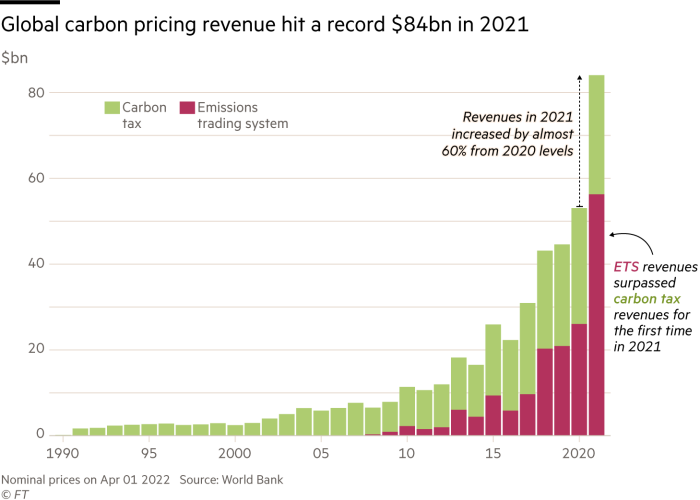

Carbon pricing generally works, if the goal is to reduce the external costs of GHG emissions that the planet and therefore the public have to incur. There are lots of different kinds of carbon pricing, the two that matter and are widely used today are carbon taxes and emissions trading systems (ETS).

Carbon taxes provision emissions by price, and ETS provision emissions by quantity. In theory and practice, both of these systems are quite good at reducing emissions while also incentivizing firms to adopt renewable practices to avoid being punished by the scheme.

Debating which is better than the other is only really interesting in a theoretical discussion. In practice, modern carbon pricing policy almost always includes both price and quantity-based measures. Policy branded as a carbon tax or as a cap and trade system usually involves elements of both in the fine text.

Economists famously love carbon taxes; the people who ‘cause’ emissions pay their fair share, and the money raised can be used to fund stuff that is good for society. Economist Gregory Mankiw loved carbon taxes so much that he created the ‘Pigou Club’, a group of economists and pundits that publicly advocate for higher taxes on carbon, gasoline, and other things that cause negative externalities. High-profile members include Elon Musk, Bill Gates, Jack Black, and Paul Krugman, among many others. Unfortunately for the club, listing those four members takes up more space than listing the club’s accomplishments.

Polling data tends to suggest that westerners are very much in favour of more ambitious carbon taxes, but when these carbon taxes are actually proposed, they often get shot down by voters. This was observed in Switzerland in 2000 and 2015, in Australia in 2014, and in Washington State in 2016 and 2018. The same goes for cap-and-trade schemes, by far the most successful is the EU-ETS, but when the Obama administration tried to implement a nationwide ETS, it failed.

There are a few typical criticisms of carbon pricing that can be fixed or adjusted for with smart policy. When I was an undergrad, I argued in a policy class that carbon taxes are regressive, because poor households typically spend a higher percentage of their income on carbon-intensive stuff than richer households. Luckily, policymakers have thought of this, and these days many carbon tax policies include targeted tax credits or other rebates that minimize the issue.

ETS have a glaring flaw of carbon leakage, particularly in regions with dense country clusters. Firms under an ETS might relocate production to countries with laxer emissions standards to boost output. Astute policymakers introduced measures like output-based rebates (OBR) and border carbon adjustments (BCA) to combat this. OBR rewards efficient production by linking rebates to output levels, encouraging firms to reduce emissions without reducing production. BCA levels the playing field by imposing carbon costs on imports from countries with less stringent emissions policies, deterring firms from relocating to evade ETS regulations.

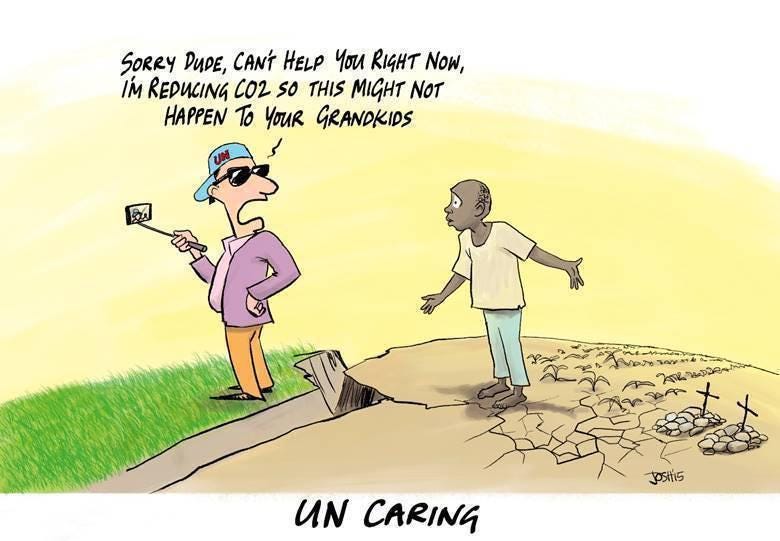

Policymakers are smart, but one issue that they cannot possibly account for in any carbon pricing scheme, is the free rider problem. Emissions are a cost that everybody on the planet has to pay. Because of this, it’s not always easy to convince the people of one specific region to adhere to a strict carbon tax, the benefits of which are mostly reaped by people on the other side of the world.

This is what some lobbying groups and pundits point to as a severe flaw of carbon pricing policy, but when researchers poll voters what their primary opposition to carbon pricing is, we find that nobody cares about free riding.

A group of economists did this in 2018. They reviewed all the relevant research on the topic and used them to identify the main points that drive public opposition to carbon pricing globally.

The personal costs are too great, especially relating to higher heating and fuel costs.

Carbon pricing can be regressive.

Carbon taxes could damage the wider economy.

Carbon taxes don’t actually discourage high-carbon behaviour.

Governments just want carbon pricing measures because they want to increase their own revenue.

Some of these notions are incorrect. Carbon pricing definitely reduces emissions, and there is no evidence to suggest that carbon pricing initiatives have had significant impacts on competitiveness. Carbon pricing can be regressive, but it doesn’t have to be.

The accuracy of public perceptions doesn’t really matter, practically speaking. In the shorter term, it’s far more important that policymakers account for these perceptions to craft carbon pricing policy that aligns with the public’s views. Here’s how they can do that:

Phase-in taxes and caps

Lower carbon prices are presumably more politically acceptable for all stakeholders. Comprehensive carbon pricing policy should take note of this and introduce climate policy that increases the price on carbon over time. This is the route that British Columbia and California have taken with their successful carbon pricing policies. A crucial point of this policy is the personal costs borne by consumers of household heating and gasoline. Research indicates that people overestimate the personal costs of carbon pricing policy. Introducing a relatively small price on carbon and gradually raising it may be less intimidating to people than a higher, static tax.

Some economists worry that phased-in carbon pricing policies incur the risk of a ‘green paradox’,1 a concept that refers to climate policies that actually end up increasing total emissions in the shorter term. Essentially, if firms expect a carbon tax to mount up in the future, they have an incentive to expand production in the present to avoid incurring increased future costs.

This is not really a practical concern. All high-emitting firms in the west already anticipate more stringent climate policy in the future; this should not discourage governments from actually enacting the more stringent climate policy.

Earmark tax revenue

The public is concerned that carbon tax revenue would just end up lining the pockets of government bureaucrats, or get spent on things they don’t care about. Carbon pricing policy that makes it explicitly clear that revenue raised will be earmarked to finance other sustainable ventures is key.

This goes against all kinds of Economics 101 theory. Any economist worth their salt will tell you that tax revenue, regardless of what avenue it was raised from, should be used to better optimize the entire tax system rather than be set aside for specific purposes. Simply put, tax money should be used on whatever it would be the most productive to use it for.

But the public doesn’t trust their governments to do this. With that in mind, it might make sense to combat this narrative by publicly earmarking the revenue raised for carbon pricing to fund other environmental ventures. There is substantial evidence of voter preference for this kind of earmarked use of revenues.

Equity and fairness considerations

People are generally concerned that carbon pricing initiatives disproportionately hurt the poor. It should therefore follow that policy proposals explicitly address this concern. The best way to do so is probably by loudly ensuring there are tax credits or rebates targeted to cushion impacts on the poor or other particularly affected constituencies.

Comprehensive survey data backs this up, people on all sides of the political spectrum tend to support using carbon-pricing revenue to ease the impacts on low-income households.

This one is a no-brainer; you’re not going to get anywhere campaigning for climate policy on the grounds of doing what's right for the world, if you don’t also explicitly address why it won’t make the poor poorer.

Local, not global!

Nobel laureate Tom Schelling characterized climate change as a classic collective action problem. It’s a long-term global issue, requiring international cooperation. Because of this, it might be hard for any one country to act, before others do so first. Alas, we return to the dreaded free rider problem.

Why should the median voter be concerned about the future generations in distant countries to the extent of accepting a steep carbon tax? Especially if there doesn’t seem to be great efforts being made to send financial aid to the same people in the same far-away lands in the present.

I think it’s time we begin to pivot from campaigning carbon pricing policy on the grounds of fighting the global climate crisis, to much more locally relevant narratives. Environmentalists have tried for decades now to convince the masses of the need to take immediate climate action to fight global climate change. It has not worked.

“Just Stop Oil” is not the path to effective climate policy. If we want voters to be interested in carbon pricing policy, it has to be contextualized to local economies. The driving narratives of climate policy must primarily focus on region-specific benefits and concerns.

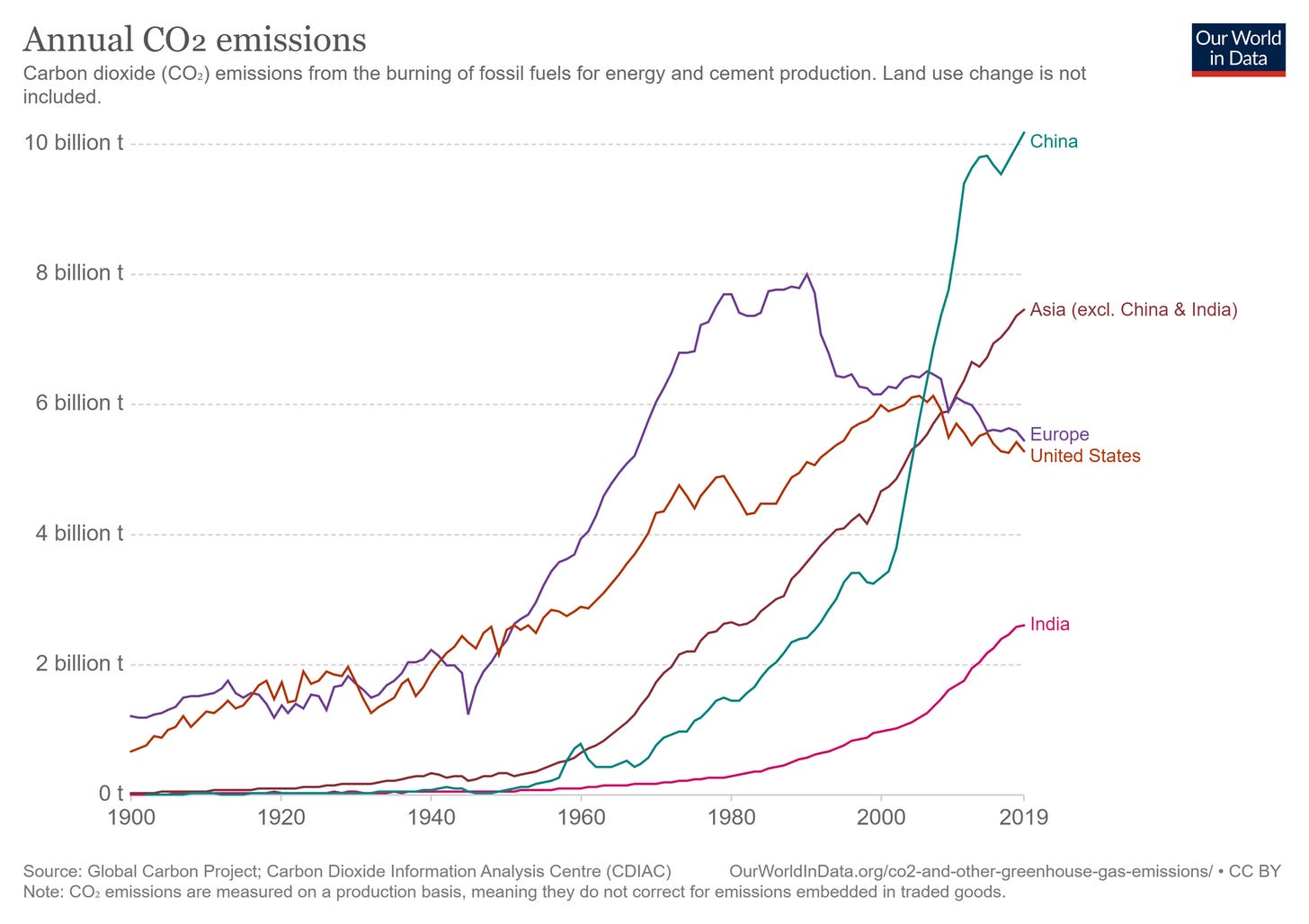

This step is especially crucial for western legislators. The vast majority of current emissions come from rapidly developing poor countries, none of which are going to introduce radically stringent carbon pricing policy any time soon.

It’s much easier to convince Belgian voters that Belgium should enact carbon pricing to encourage the local development of sustainables, than it is to convince them that they should have to pay a tax because China is emitting too much.

Ultimately this only matters if policymakers and representatives can successfully market carbon pricing policies that adopt these steps. This is no easy task. Unfortunately, a decreasing but still significant portion of the voting pools in western countries are uniformly resistant to even the most modest carbon pricing policies. Good marketing probably won’t sway these folks.

Economists must recognize that their perfectly efficient and theoretically strong policy prescriptions are not necessarily convincing in practice. A pigou tax sounds great in conversations, but if the public thinks that such a tax is regressive or an excuse to increase government revenue, steps must be put into place to quell these concerns.

Marketing politically viable carbon pricing policy is an immense challenge. It's not easy to bridge the gap between economic theory and public acceptance. Listening and integrating public feedback into policy design is the only way to demystify these concepts and gain broader support.

The green paradox does not describe a paradox. There is nothing paradoxical about it. It’s called that because it’s named after a book, and the word paradox looks good on book covers.